Last Thursday, I spoke in a debate at the Cambridge Union on the motion ‘That this house would scrap the Lords’. There were three speakers for the motion: Darren Hughes (chief executive of the Electoral Reform Society), Kezia Dugdale (former Scottish Labour leader) and a student. Speaking against was the Green peer Baroness Jones of Moulsecoomb, cross-bencher (and the first Lord Speaker) Baroness Hayman and me.

Last Thursday, I spoke in a debate at the Cambridge Union on the motion ‘That this house would scrap the Lords’. There were three speakers for the motion: Darren Hughes (chief executive of the Electoral Reform Society), Kezia Dugdale (former Scottish Labour leader) and a student. Speaking against was the Green peer Baroness Jones of Moulsecoomb, cross-bencher (and the first Lord Speaker) Baroness Hayman and me.

Before the debate, there was an indicative vote taken: the students, I was informed afterwards, split roughly 50:50 on the motion. When the vote was taken at the end of the debate, the result was: Ayes 18 Abstentions 41 Noes 73. It was a remarkable victory and I think bears what was noticeable about the evidence submitted to the Royal Commission on the Reform of the House of Lords in 2000: the people who know more about the Lords tend to be the most supportive. When you explain to an audience what value is added by the House of Lords, they move in favour of retaining it to fulfil its functions.

I opened not by defending the Lords, but by making the positive case for the House. I began with two propositions. First, that good law is a public good. Second, that form should follow function. The two in combination make a powerful, I think compelling, case for the House. I developed the points in terms of what the House did in ensuring law was as good as it could be in delivering on what it was intended to achieve. The fact that the House of Commons is elected is why it should determine the purpose of legislation. The fact that it is elected is why it cannot devote time to making sure it is crafted in such a way as to ensure it fulfils its purpose. That is the function of the Lords and the composition is crucial to enabling it to fulfil it effectively. As such, it complements the Commons. It does not conflict with it, which would render the House objectional. It does not duplicate what it does, which would make the House superfluous.

In the latter half of the my speech, I responded to the usual arguments deployed against the house, but which are not actually arguments for scrapping it. That it is too large is an argument for reducing its size, not abolishing it. The fact that there are problems with the nominations process is an argument for reforming the process (not least through passing my House of Lords (Peerage Nominations) Bill), not abolishing it. As for the argument that the House is undemocratic, I explained why that is not self-evidently true and made the democratic argument for an appointed second chamber.

It was twenty years since I spoke against a similar motion at the Oxford Union. The principal speaker for the motion was the late Earl Russell. I am pleased to say that the students also on that occasion voted down the motion.

It is gratifying that the value of the House of Lords is recognised in what Blackadder recognised as the nation’s three great educational institutions. Where Hull students lead, those of Oxford and Cambridge follow.

Commission report on blended learning. The report examines how to implement successfully digitally-enhanced blended learning. The challenge is substantial.

Commission report on blended learning. The report examines how to implement successfully digitally-enhanced blended learning. The challenge is substantial. On 7 March, the House of Lords debated a motion, moved by Lord Blunkett, to take note ‘of the contribution of higher education to national growth, productivity and levelling-up’. Given the number of peers who had signed up to speak, each backbench speaker only had five minutes.

On 7 March, the House of Lords debated a motion, moved by Lord Blunkett, to take note ‘of the contribution of higher education to national growth, productivity and levelling-up’. Given the number of peers who had signed up to speak, each backbench speaker only had five minutes. amendment to an SNP motion, going against convention and the advice of the Clerk of the House, a number of MPs tabled a motion of no confidence, utilising the only means permissible to criticise him.

amendment to an SNP motion, going against convention and the advice of the Clerk of the House, a number of MPs tabled a motion of no confidence, utilising the only means permissible to criticise him. range of proposals. Some had a historical tinge – I suspect not all readers will know who ‘J. R. Hartley’ was (and I rather hope that I don’t end up having to ‘phone round booksellers to find a copy of the book!) – and others seemed to ascribe me a more sinister status based on Nadine Dorries’, er, reflections. Some were also even more topical in referring to revelations in a Dutch translation. If only there was a Dutch translation… Mind you, a year or so ago I did find a copy of Politics UK in an Amsterdam bookshop, so there is hope that the book, even untranslated, will find its way to the Netherlands. As followers on X/Twitter will know, it has found its way to Switzerland.

range of proposals. Some had a historical tinge – I suspect not all readers will know who ‘J. R. Hartley’ was (and I rather hope that I don’t end up having to ‘phone round booksellers to find a copy of the book!) – and others seemed to ascribe me a more sinister status based on Nadine Dorries’, er, reflections. Some were also even more topical in referring to revelations in a Dutch translation. If only there was a Dutch translation… Mind you, a year or so ago I did find a copy of Politics UK in an Amsterdam bookshop, so there is hope that the book, even untranslated, will find its way to the Netherlands. As followers on X/Twitter will know, it has found its way to Switzerland. The posts on this blog have covered a range of issues as well as offering comments on my parliamentary work and providing light relief through a caption competition. Some of the topics have been superseded by events – such as the Fixed-term Parliaments Act (on which I did several posts) being replaced by the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Act. Others remain of relevance and I felt there may be merit in drawing together those that are likely to be of interest to teachers and students of politics. They comprise a mix of analysis, opinion and factual reporting.

The posts on this blog have covered a range of issues as well as offering comments on my parliamentary work and providing light relief through a caption competition. Some of the topics have been superseded by events – such as the Fixed-term Parliaments Act (on which I did several posts) being replaced by the Dissolution and Calling of Parliament Act. Others remain of relevance and I felt there may be merit in drawing together those that are likely to be of interest to teachers and students of politics. They comprise a mix of analysis, opinion and factual reporting.  Do we need a ‘written’ constitution?’

Do we need a ‘written’ constitution?’  The House of Lords

The House of Lords The 1922 Committee

The 1922 Committee

help sales of the book by being especially active in the past year) and by John Rentoul of The Independent, who noted that Sir Graham had used to opportunity to declare publicly that he supported the election of the Conservative leader, at least when in government, reverting to MPs. In speaking, I stressed the fact that the 1922 Committee was an important political body, but one that had largely been hidden in plain sight. Mine was only the second book to be published about the 1922. The first was published in 1973 to mark its 50th anniversary. A lot has happened in the past fifty years, indeed in the past five. I am pleased to say that the publisher did a brisk trade in selling copies of the book.

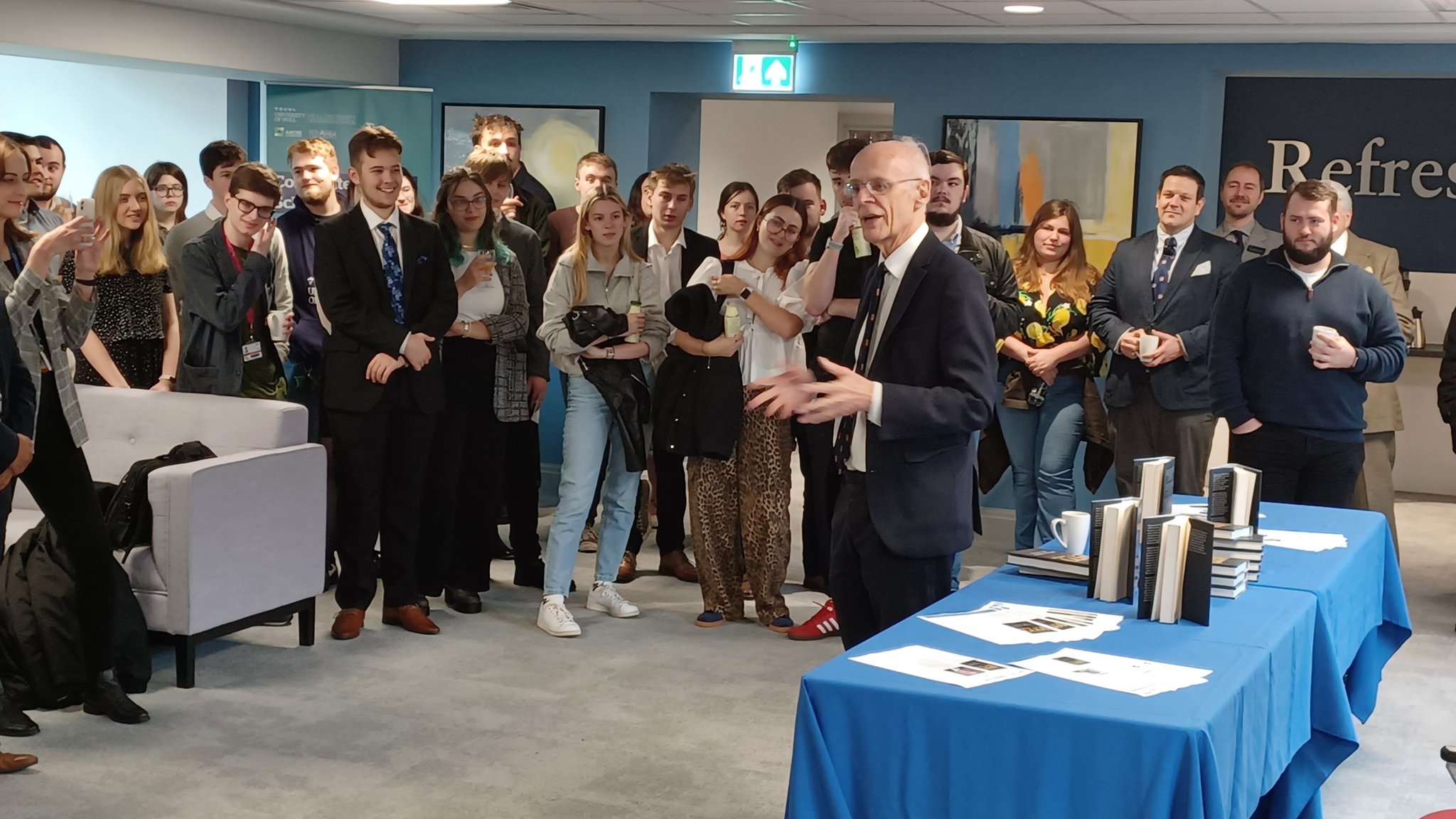

help sales of the book by being especially active in the past year) and by John Rentoul of The Independent, who noted that Sir Graham had used to opportunity to declare publicly that he supported the election of the Conservative leader, at least when in government, reverting to MPs. In speaking, I stressed the fact that the 1922 Committee was an important political body, but one that had largely been hidden in plain sight. Mine was only the second book to be published about the 1922. The first was published in 1973 to mark its 50th anniversary. A lot has happened in the past fifty years, indeed in the past five. I am pleased to say that the publisher did a brisk trade in selling copies of the book. At the reception on campus, there was also a splendid turnout, not least of students. I reiterated some of the points made at the Westminster launch as well as addressing some of the myths about the 1922. As with the Westminster reception, not only was there a brisk sale of the book, but also a queue of people seeking signed copies.

At the reception on campus, there was also a splendid turnout, not least of students. I reiterated some of the points made at the Westminster launch as well as addressing some of the myths about the 1922. As with the Westminster reception, not only was there a brisk sale of the book, but also a queue of people seeking signed copies. Various media were sent bound copies of the initial proofs in order to facilitate reviews to precede or coincide with publication. One has already appeared, a generous one in The Sunday Telegraph (on 17 September) by Simon Heffer. I was enormously gratified both by the content as well as the prominence of the piece. The book, he says in opening, ‘exhibits impeccable scholarship and a degree of charm’. The good news is that this is not like an extract taken out of context to promote a show.

Various media were sent bound copies of the initial proofs in order to facilitate reviews to precede or coincide with publication. One has already appeared, a generous one in The Sunday Telegraph (on 17 September) by Simon Heffer. I was enormously gratified both by the content as well as the prominence of the piece. The book, he says in opening, ‘exhibits impeccable scholarship and a degree of charm’. The good news is that this is not like an extract taken out of context to promote a show.